back

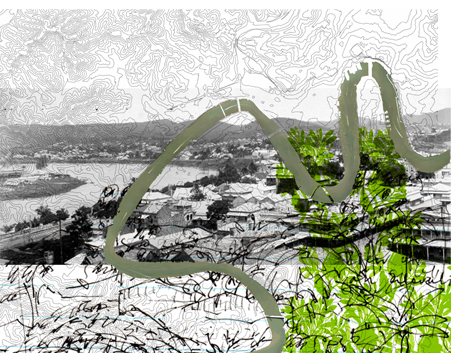

The process of constructing the first envisioned city map begins with an aerial view and a focused frame of the

contemporary subtropical city of Brisbane.

In order to identify the subtropical city we overlay the aerial view with the experience from ground level which

gives another perspective of the lay of the land where, from here, tree-clad ranges, ridges, hills and gullies fold

towards the river and trees stamp their “greenness” onto each vista and into the Subtropical City’s core – its

very identity.

The Sedimentary City process also uses the observations, perceptions and representations of others to map

the identity of the city- the scientists, poets and other artists in our community who define this city in terms of

its memorable landscape – views of its hills, ridges, and mountains, the greenness of its trees and the snaky

meander of its river. (Fuller, 2007)

David Malouf recalling experiences of the place of his childhood home writes:

“The first thing you notice about this city is the unevenness of the ground. Brisbane is hilly. Walk two hundred

metres in any direction outside the central city (which has been levelled) and you get a view – a new view. It is

all gullies and sudden vistas”…”The key colour is green, and of a particular density: the green of mangroves

along the riverbanks, of Moreton Bay figs, of the big trees that are natives of this corner of Queensland, the

shapely hoop-pines and bunyas that still dominate the skyline along every ridge. … “So much then for the lay of

the land: now for that other distinctive feature of the city, its river. Winding back and forth across Brisbane in a

classic meander, making pockets and elbows with high cliffs on one side and mud flats on the other, the River is

inescapable. It cuts in and out of every suburb, can be seen from every hill.” …”I know of no other city like it.”

(Malouf,1990)

Here, the poet claims that, identifying with the landscape qualities of the place we inhabit reaches to the very

core of belonging and remembering.

In the Subtropical City, the survival of its identity, as such, is dependent on the survival of the extent and the

continuity of its landscape – its hills, its trees its river and its greenness.

The Brisbane City Council’s draft Urban Open Space Strategy (BCC, 2007) outlines all the significant factors

and defines the sustainability and survival of the sub-tropical city in terms of biodiversity, landscape and

recreation - this view however is largely in reaction to population growth and urban consolidation and

currently provides no clear direction or definitive future city plan.

The Sedimentary City project undertakes a mapping process with the question: ‘Exactly where in the

Subtropical City are greenspaces that sustain its survival and its identity?’

Although we have found no clear data for answers to this question an approximate figure and distribution of

greenspace in the city can be gauged from figures given by the Brisbane City Council (BCC, 2009) for the city’s

tree cover, which is approximately forty five percent. Twenty seven percent of this amount however is

accounted for in residential suburban areas of which 70% includes the trees and gardens of the suburban house

that are increasingly put at risk by the trend to maximize building area and rezoning for dual or multiple

occupancy. The remaining 30% includes street tree planting and public open space, which along with parts of

the remaining 18% of tree cover in the city (of which no clear location is given) are considerable areas of what

BCC terms ‘organized greenspace’, in contrast to ‘unstructured greenspace’, (BCC, 2007), all with areas of

other inherent limitations or restricted access and all vulnerable to future loss.

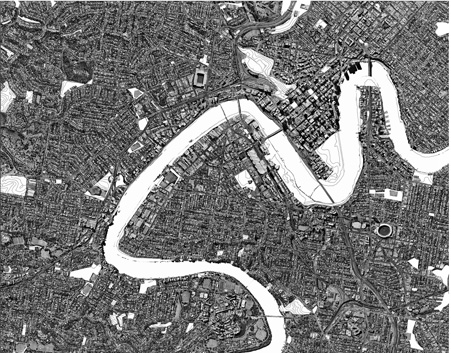

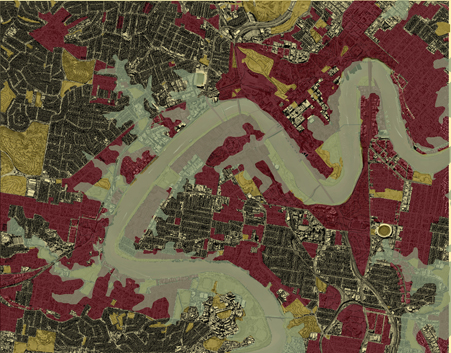

With this in mind, we begin a process of mapping-analysis with regard to the city’s greenspace within our

selected frame of the city. Firstly we map where and what the perceived extent of the city’s green space might

be.

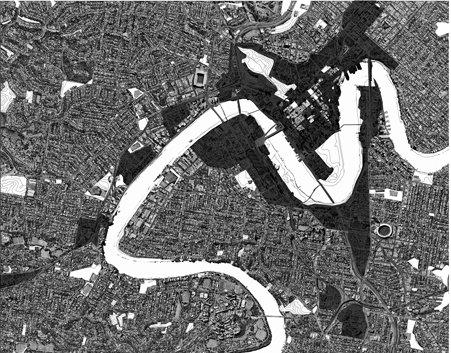

We then map the city’s essential greenspace by discounting all areas that are: not publically owned; ‘structured’

or otherwise limited such as cemeteries etc; leasable such as sports ovals; marginal zones like street trees etc –

in order to discover where and how much of this greenspace there is left. This reveals a map of today’s city

and its public, ‘unstructured’ greenspace – treed places freely available to the citizen city - a map of severed

fragments of green space, visually and physically discontinuous in the city and unconnected to the wider ecology

of the natural environment.

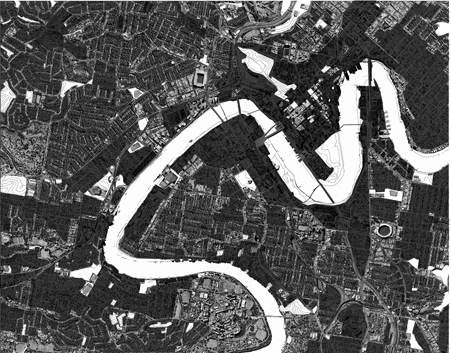

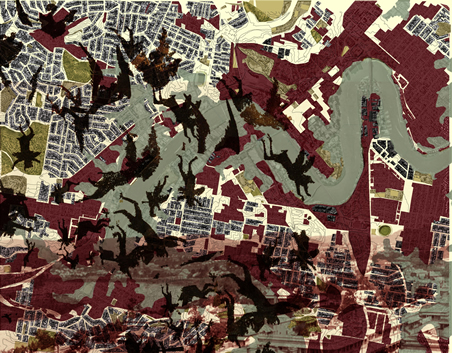

The Sedimentary City process now looks to the future - mapping layer by layer - as we imagine the outcome of

today’s city plan - a plan driven by expectations of absorbing increasing populations to be interconnected by

communications and mobility networks converging on the central business district.(BCC,2006)

In our Contemporary City,

unlimited heights are proposed for development in the central city core and tall buildings line up along

suburban railway lines and along riverbanks where they overshadow the river and adjacent parkland. The city

consolidates, in-fills, increases its building stock and expands its infrastructure. Taller buildings and larger

footprints block views, overshadow marginal ground and squeeze out large trees further diminishing the

remaining fragments of the city’s green space: ‘Where will future citizens find respite from city fatigue?’

The consequences of diminishing greenspace in the city include the further loss of trees, loss of biodiversity,

loss of citizen wellbeing and health, loss of capacity to respond to more extreme weather events, loss of shade,

loss of amenity and loss of the sub-tropical city. Gone is the continuity of greenspace supporting the ecology

of the natural environments, gone are the urban forests that that once linked the city to its wider setting and

surrounding ranges.

In light of the diminishing natural environment and long-term climate forecasts: ‘How will the future city

maintain environmental security and amenity for its citizens?’

We conclude this first part of the Sedimentary City process with the imagined “Envisioning One”

Transformed, today’s City of Subtropical Gardens has become the Concrete Jungle of the future, where,

alternating with extreme weather cycles, it emerges from time to time as Inferno City or Flood City.

In future El Nino years we imagine a scorched and radiant city layer where the vanquished subtropical jungle

has fully given way to the triumphant concrete jungle where citizen of the future inhabit the Inferno City.

In future El Ninja years we imagine storms which lash the city with frequent tropical downpours causing intense

overland flows, creating river flooding contributing - with storm tide flooding - to cause disaster. (Newman,

2008) Emerging during the long El Ninja era is Flood City where engineering and planning policies have covered

the earth with flow path obstructions, concentrated building clusters, rail embankments, bridges, tunnels and

networks of pipes enclosing the remaining waterways of the city.

Envisioning One presents us with a nightmare image - the current, unfolding scenario – for which we seek an

alternative outcome through the next cycle of the Sedimentary City process

Envisioning 2 >>>

|

|