back

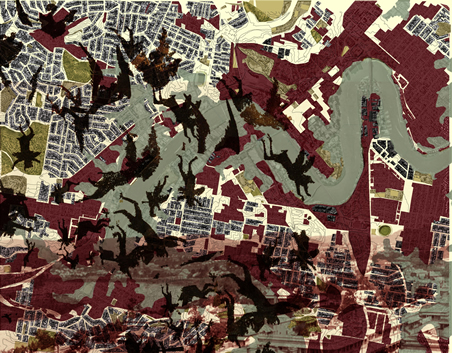

Now, through the Sedimentary City process, with a fast-forward layering, we can look from the First City map

to the map of the forecast Inferno City from Envisioning One to see that we need an alternative to both of

these.

Envisioning Three sets out to propose directions for an alternative future layer for the sub-tropical

Sedimentary City.

Returning to look at the provisional maps, of First City and Inferno City, there is, dominant in both, the

common bold figure of the flooded river, a powerful symbol – an emblem watermarked across each map.

It is this emblem – the footprint of the floodplain with its contributing creeks and watershed that triggers the

process of revealing through city layers, the steps towards implementing the next layer - tomorrow’s city.

Beginning with the contemporary city we reveal today’s city layer in flood.

Forecasts predict more extreme weather patterns in the future, extreme flood events are predicted when heavy, continuous rainfall will cause river levels to rise and local surface water to concentrate in low laying land. Damage from floodwater will be amplified in areas with hard impervious surfaces - and intensified where water flow is dammed by barriers, increasing the speed, and altering the direction of floodwaters. Furthermore, in extreme circumstances, the co-incidence of sea level rise combined with a high tide and storm surge is forecast to further increase flood heights.

To avoid the flood plain, the ‘Second City’ of Brisbane was founded on high ground and flood-prone land remained undeveloped in many areas. In these early layers the human footprint was more independent of the floodplain, the floodplain being a natural environment as a distinct, continuous and absorbent watershed. By contrast, a review of the present city layer reveals that the footprint of the once-green floodplain is now largely transformed by an overburden of buildings and infrastructure predominantly for economic gain.

This is a transformation made possible by engineering works undertaken to bury the creeks in pipes, drain the swamps, to cut and fill, construct earthen levees and seal in the earth with hard surface materials – and in each undertakind reducing the efficiency of the city’s watershed and by piping the creeks – thereby restricting and removing one of the key landscape elements within the city’s ecology.

With the Sedimentary City process we return to the first layer to review the floodplain of the First City to find

what has been lost along the way and to consider its reinstatement. This way of layering the city demonstrates

the First and the Contemporary city in terms of Grumbach’s “La Ville sur La Ville” - city on city (Grumbach,

1998), and identifies the direction we would adopt for “survival – [and] implementing tomorrows city”.

We reintroduce and adapt elements from the First City, for their contribution to the next layer of the city – a city forecast for an infinitely growing population. In this future City its citizens live at a new existenz-minimum in a sustainable equilibrium with the environment. This redistribution governs the spread of density and degree

of consolidation on the land between the mountains and the floodplain, assuring the long-term survival of the

city’s natural environment and, with this, securing the physical and metaphysical wellbeing of the citizenry.

Returning to the floodplain we begin the process of editing (adding / subtracting) by re-introducing, over time,

the network of creeks discovered in mapping the First City, reinstating / re-engineering them for future

environmental gain. Pipes are cracked open to daylight the creeks, the network of gullies and creeks reconnect

the mountains and ridges of the City to its wide serpentine river.

The creeks and its watershed are re-formed and reunited with their landscapes of swamps and ponds so

significant and integral to the efficiencies of flood and drought dynamics for the well-being of the City’s

landscape ecology – as Turpin writes in the Clear Paddock Creek project, where “(This)… engineering

expediency (has) undermined the complexity of fragile ecosystems and made urban stormwater the major

pollutant of our waterways and oceans. By contrast, natural creek systems sustain biological diversity and

wildlife habitat and are superior managers of quantity and quality of urban stormwater “. (Turpin in Johnson,

2004)

Pathways from the First City layer are reinstated. Citizens in the consolidated City find themselves within easy reach of creek-side pathways leading downhill to the riverbank or uphill to ridge lookouts and further on up to mountain forests and wilderness for moments of solitude and respite from city life.

Trees from the First City layer are selectively reinstated for suitability in dry and wet conditions to fill the

floodplain creating forests in the future City. Forests cool the city, absorb toxins, offer sustaining habitat, bear

fruit, bring visual amenity and re-establish the experience of living in the subtropical landscape.

The floodplain landscapes with their mountain/ridge backdrops form a consolidated city green space of a scale to offset the intensity of future urban consolidation. The future city layer would retain existing pocket parks and many structured green spaces would be shared, re-evaluated or liberated (for food, fibre and water or like) when sporting fields are reassessed in terms of their environmental impact and re-housed accordingly.

Presenting envisioned, alternative futures for the city has hinged on the idea of restoring its beauty, safety and amenity through the natural environment.

Citizens of Inferno City have lost sight of their Subtropical City. Citizens of the First City are looking for their Subtropical City and the citizens of the alternative future city can only regain the Subtropical City through vigilance.

In conclusion,

Italo Calvino’s “Invisible Cities” ends with a dialogue between Marco Polo - the inventive storyteller - and the Great Kublai Kahn, Emperor of the Tartars, who enquires about cities of the future:

“You, who go about exploring and see signs, can tell me toward which of these futures the favouring winds are driving us.”

The Great Kahn scanning his atlas, first for maps of promised lands such as “… New Atlantis, Utopia, the City of the Sun, Oceana, Tamoe, New Harmony, New Lanark, Icaria” and then turning to “… the cities that menace in nightmares and maledictions: (such as) Enoch, Babylon, Yahooland, Butua, Brave New World.” …finally he exclaims:

“It is all useless, if the last landing place can only be the infernal city, and it is there that, in ever-narrowing circles, the current is drawing us.”

Marco Polo replies with the words: ”The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together.

There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it.

The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of the inferno are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.”

References

Italo Calvino, “Invisible Cities”, Vintage, London, 11997 (first published in Italy, 1972)

Peter Myers, “The Third City”, in Architecture Australia, Jan-Feb, 2000.

Louise Noble, “Brisbane : une analyse morphologique”, unpublished thesis

Kevin O’Brien, “Sep Yama: Finding Country”,

Antoine Grumbach, “La ville, processus et langage”, Project Urbain, 1998, Dec., no.15, 1998.

Antoine Grumbach, “ …..” in AD, Profile 20, Roma Interrotta, 1979, v.49, n.3-4.

Richard A. Fuller. “Feeling the Pinch of Compact Cities”, BBC News, http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/- /2/hi/science/nature/6754549.stm Published: 2007/06/15 12:06:07 GMT.

David Malouf, “A First Place: The Mapping of a World”, in “Johno, Short Stories, Poems, Essays and Interviews”, ed. James Tulip, UQ Press, 1990.

Brisbane City Council, (BCC) “Open Space Strategy”, , 9 April, 2009.

Brisbane City Council, (BCC), “Urban Open Space Strategy”, in, “Draft City Shape, Implementation Strategy, The local Growth Management Strategy for the City of Brisbane, Consolidated Planning Report, 26 April 2007”, pp32-34.

Brisbane City Council, (BCC) "Brisbane City Centre Master Plan 2006-2026: A vision for the Future of our city's centre" August 2006

Campbell Newman, Lord Mayor, ‘Important update on flood preparedness’, BCC, 12th June, 2008.

Map c.1824-5 (Lt. Stirling), “Skirmish Pt. to Cape Byron”, QSA Item 714407. Stirling’s survey of the Brisbane

River was carried out between 1-5 December 1823 and the chart accompanied Oxley’s report to Governor

Brisbane in January1824. (Steele p106.) Three journeys to Brisbane took place in the period Nov/Dec 1823-

1824. Surveyor General John Oxley and assistant Robert Stirling mapped the Brisbane River during 2/3/4 Dec

1823.

‘The Selected Works of Thomas Welsby’, ed. A.K. Thomson, The Jacaranda Press, Brisbane, 1967, pp14-16.

H.J. Hall, ‘20,000 Years of Human Impact on the Brisbane River and Environs’, in, ‘The Brisbane River: a sourcebook

for the future’, eds. Peter Davie, Errol Stock, Darryl Low Choy, Moorooka, Qld: The Australian Littoral

Society in association with the Queensland Museum, 1990, pp175-181.

‘Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland’, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1983, pp317-323.

Elizabeth Dann, ‘Aboriginal Place Names in Brisbane: misplaced, mispronounced and misunderstood’, in,

Brisbane History Group Papers No9, Brisbane, 1990, Chapter 12, p79.

J.G. Steele, ‘Aboriginal Pathways in South East Queensland and the Richmond River’, UQP, St. Lucia, 1984.

J.G. Steele, ‘The Explorers of the Moreton Bay District, 1770-1830’, St. Lucia, UQP, 1972.

Turpin and Crawford, “Restoration of the Clear Paddock Creek”, in, Chris Johnson, Greening Cities,

Government Architects Publications, Sydney, 2004.

top

|

|